3 Method

3.1 Research design

A pragmatic grounded theory design was used to conduct the present study (Chamberlain-Salaun, Mills and Usher, 2013). Although originating in social science fields, this approach has become more common in the health sciences to extract understanding from communications with participants immersed in the area of study (Levitt et al., 2018). Such an approach is also practical in topics where prior research is sparse, and a researcher is aiming to follow an inductive process rather than entering with predetermined theories.

3.2 Participant recruitment and characteristics

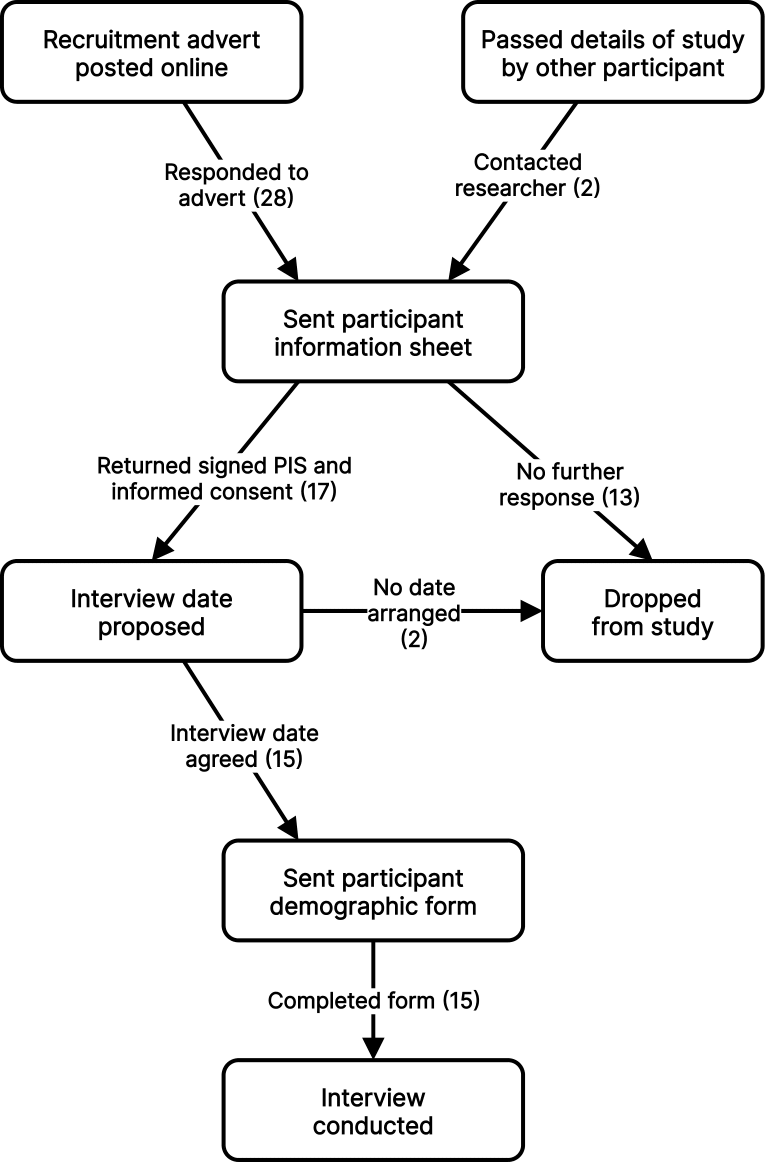

Following ethical approval by the London Metropolitan University School of Human Sciences Research Ethics Review Panel, parkour coaches were recruited using purposeful and snowball sampling techniques (Strafford et al., 2020). A flow chart of the participant recruitment process is reported in Figure 3.1. Recruitment for the study was initially advertised through parkour coaching online social groups and the researcher’s own personal social media accounts. Participants were required to have experience coaching parkour, although no minimum amount or current status requirements were set to try and capture a broad variety of experience levels and viewpoints. Following initial recruitment, two participants also voluntarily passed details of the study to colleagues for further recruitment. All participants signed informed consent forms prior to interviewing and were offered anonymity when reporting interview contents. Participant demographic information, including their age, gender, location, and parkour training and coaching experience, was gathered using online form software (Airtable.com, San Francisco, Formagrid Inc.) submitted by participants in advance of their interview.

Figure 3.1: Participant recruitment flow chart.

Fifteen parkour coaches were interviewed (male = 11, female = 4, age [mean ± sd]: 26.5 ± 7.5 yr, parkour experience: 9.2 ± 4.5 yr, coaching experience: 5.1 ± 4.7 yr). Full participant characteristics are reported in Table 3.1.

| ID | Gender | Country | Age (y) | Parkour | Coaching |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Female | UK | 35 | 7.0 | 2.0 |

| 3 | Male | Slovakia | 22 | 8.0 | 3.0 |

| 4 | Male | USA | 39 | 16.0 | 15.0 |

| 5 | Female | USA | 26 | 3.5 | 1.5 |

| 6 | Male | UK | 20 | 6.5 | 1.0 |

| 7 | Male | USA | 23 | 9.0 | 3.0 |

| 8 | Male | Austria | 24 | 10.0 | 5.0 |

| 9 | Male | Norway | 17 | 2.5 | 0.3 |

| 10 | Male | UK | 42 | 15.0 | 13.0 |

| 12 | Male | USA | 19 | 6.0 | 2.0 |

| 14 | Male | USA | 22 | 13.0 | 4.0 |

| 16 | Female | USA | 29 | 7.0 | 3.0 |

| 17 | Female | USA | 27 | 9.0 | 6.0 |

| 18 | Male | Turkey | 32 | 18.0 | 13.0 |

| 19 | Male | Slovakia | 21 | 7.0 | 4.0 |

3.3 Interview process and data analysis

Interviews were conducted via video calls using Zoom (version 5.5.4, San Jose, Zoom Video Communications Inc.). Interviews lasted between 44 and 96 minutes (mean: 63 ± 14 min). All interviews were conducted in a semi-structured format, with key questions to be asked while allowing for flexible diversions into individual details and sub-questions as the conversation developed. All interviews began with participants being asked for a brief description of the kong vault in their own words before probing questions were used to investigate further aspects of this description. Either as a direct result of these probing questions or by transitioning into new topics where appropriate, interviews then explored the participants own understanding of how a kong vault is performed, including identifiable features of the vault, a breakdown of its execution, how the vault may be used and in what situations, and participant experiences in learning and coaching the vault. The researcher had professional experience in the field of parkour coaching and was able to allow conversations to develop naturally in terms familiar to the interviewee, further building trust and rapport. Given the pragmatic approach to research design, the structured components of the interview process were reviewed after each participant and updated if other common relevant topics arose.

All interviews were recorded in their entirety using the built-in recording feature of Zoom and transcribed into text format. A mixed transcription method was used, with initial transcription taking place using automatic transcription software (Otter.ai, Los Altos, Otter.ai Inc) before being manually checked and corrected where necessary. Interview transcripts were analysed using NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis software (version 1.3.2, Massachusetts, QSR International) for both initial and follow-up coding stages as data was gathered and coding themes developed (Creswell and Creswell, 2020).

Initial coding used thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006) to identify and extract the various common language descriptions given to the kong vault across a variety of dimensions, including its phases, permutations, goals, uses, and execution, and generate themes relating to each of these dimensions. Follow-up coding then considered how these themes and descriptions could be combined or connected, linking them to build an overview of the technique and the factors affecting performance. As per the research design, a pragmatic method using both inductive and deductive approaches was applied in coding, with some statements by participants expressing clear meaning (inductive) while other statements were interpreted through a theoretical biomechanics perspective (deductive) to inform their contribution to the understanding of the kong vault.

3.4 Model creation and validation

Recruitment, interviewing, and coding cycles continued until it was perceived that data saturation had been achieved, wherein new data collected was no longer revealing new meaningful features, only confirming those already identified (Aldiabat and Le Navenec, 2018). Once data saturation was reached, the phases, goals, and coaching cues identified for the kong vault were compiled into a deterministic model diagram. As described in Hay and Reid (1988), a single identified outcome measure was placed at the top of a block diagram and subsequently broken down into component mechanical variables in the level below. Each variable was further broken down in subsequent levels until a variable could not be further usefully deconstructed into smaller components and each level of the diagram was explained by the level below it. Variables were broken down by a mix of information gained from the interview process (deductive) and the researchers own biomechanics knowledge and research (inductive).

An independent critical friend approach was used to ensure research rigour and encourage reflexiveness during the analysis and model building stages (Smith and McGannon, 2018). Identified themes from interviews were discussed with an external and independent experienced parkour coach (male, UK, age: 32 yr, parkour experience: 12 yr, coaching experience: 6 yr) throughout the analysis process, along with the thoughts and interpretations formed by the researcher to build the deterministic model of the kong vault. Their role was not to contribute to the data being analysed but rather to provide a source of independent thought on the interpreted elements of the interview contents and to provide a secondary source of validation to the finalised model (Strafford et al., 2020). This approach ensured the final model was not simply the researcher’s own preexisting notions of the nature of the kong vault filtered through cherry-picked participant responses but rather a consensus reflection of the themes drawn from the interview process.